My flatmate and I have a dinner-time tradition, not unlike many in our position. We get home from work, catch up while cooking ourselves some dinner and then instinctively turn on Netflix when we sit down to eat. You gotta have something to watch, right? Classic unwind.

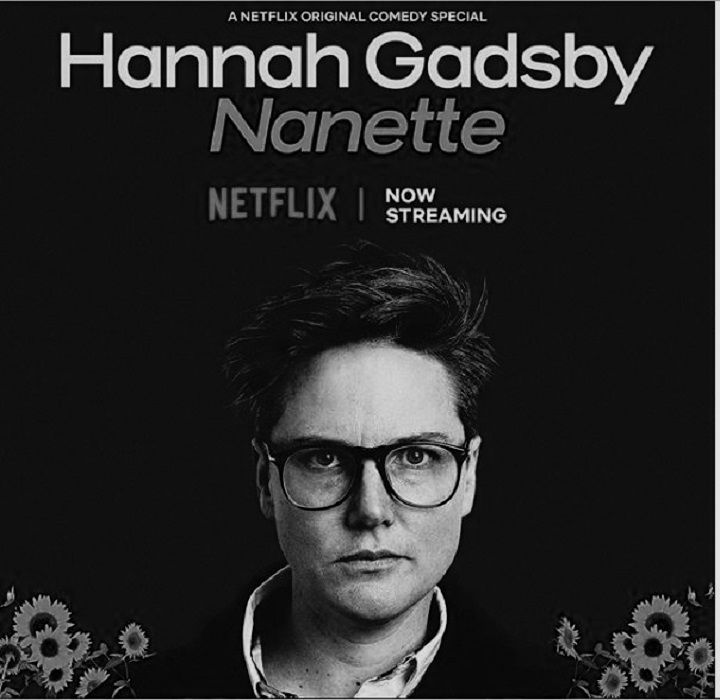

And this random Tuesday was like so many others, except that a friend suggested we watch Nanette and we thanked our stars for the fact that we already knew what we wanted to watch instead of the endless black hole that is the Netflix search.

But I’ve set the scene enough to have you understand that the next hour of viewing time was not in any way what we expected going in—and thank God for that, because what followed opened my eyes and punched me in the gut all at the same time. And this is precisely why I wanted to write about it today. Not as a trite piece on why it’s a must-watch or why Hannah Gadsby is the next feminist queen, but as a deeply personal essay on how this show made me take pause and think like no piece of entertainment has in a long time.

The whole experience felt like getting to know someone from scratch. At first, it was all well and good. There were jokes, haha’s were had and it felt light, happy and “chill”. We all lurrrve “chill”, don’t we? No one wants to deal with anything “heavy” if they can help it. But then slowly as you get to know more and more about a person or you spend more time with them, you start to peel back the layers and see all the flaws and the damage and very real stuff. And this core of a person will do one of three things.

- It will freak you out enough to skedaddle. Or in this case, turn off Netflix.

- You will stick around to see how it plays out, but the whole thing will make you so very uncomfortable that you won’t want to really think about it after.

- Or, it will be like a punch in a gut and you’ll be in awe of how raw and real communication truly allows you to see a person and understand their story.

No points for guessing which one of the three happened to me. I was caught absolutely off-guard as the first 20 minutes of tried-and-tested self-deprecating humour suddenly turned like the tide. She stopped short and said that she was serious about quitting comedy and what proceeded was the most honest expression of a personal story.

The Anatomy Of A Joke

The thing that she points attention to right after her series of anecdotal jokes about her past, is the fact that the very construct of a joke works off of the need to build tension and release it. And how you may wonder is tension built? Well in contrast to a story that has a beginning, middle and an end, a joke only has only two – a setup and a punchline and leaves out the crucial part of closure. For a joke to successful and elicit a laugh, you need to end at the apex. It cuts out the ending where the complexity and context of the story live. And that’s what makes jokes harmful. So while she starts her special with these anecdotal jokes, she circles back to them and actually tells the story. Like the one about a drunk dude thinking she was another dude (because of her appearance) hitting on his girl and threating to hit her only to come back and apologise because he realized she was a woman. Classic. But then when she circles back (a callback in comedian terminology) and tells the full story about how he did come back when he realised she was a “lady faggot” and beat her black and blue, it suddenly dawns on you that you laughed at only half the story. This brutal experience was cut short for the sake of releasing your tension and giving you the permission to laugh. And in going back and undoing the punchline, she allows you to truly see the story in its truest form. Instead of using humour to deflect the tension, tell half the story and trivialise the experience overall.

Genuine Communication

Like this, she goes back and undoes all the tropey punchlines of the first half of her set, now delving into the very real stories and very real experiences of her life as a lesbian in 1990s “Bible-belt” Tasmania. And while that leaves you feeling uneasy and particularly shitty for laughing at these “jokes”, it is essential because it is only through genuine communication that people are truly understood. She even gets angry on stage and lets that show, because it is truly time that people started to pay attention. But towards the end, she concedes that anger is not the answer saying, “It knows no other purpose than to spread blind hatred, and I want no part of it. I don’t want to unite you with laughter or anger. I just needed my story felt and understood.” And that is what it’s all about.

Taking A Stand

Finally, (and here’s why I believe what I said in the title of this article) the most important lesson I took away from this Netflix special is that you have to stop partaking in the behaviours that are detrimental to your wellbeing. What I mean by that is that Hannah decided that it was time to quit comedy because in her words, “I built a career out of self-deprecation, and I don’t want to do that anymore. Because you do understand what self -deprecation means from somebody who already exists in the margins? It’s not humility. It’s humiliation.” I couldn’t have said it better myself. And in the same way, women need to stop being the biggest victims to the patriarchy and saying things like, “I’m not a feminist.” because that simply means that you are partaking in the very behaviour that is putting you down. So, just like Hannah Gadsby, I am here to say #ItEndsWithMe.